Garry Knox Bennett is a furniture designer maker and self proclaimed “blue-collar guy”. Living and working out of California for most of his life he has been designing and making furniture for over 40 years.

Garry was born in 1934 in Alameda; his grandfathers and great-grandfathers on both sides were sea captains. At an early stage in his schooling a substitute teacher commented to him that his “penmanship is so beautiful you could be an artist,” and Garry decided on the spot that when he grew up he would become one.

Enrolling at the California College of Arts in Oakland in 1959 to study art academically, learning how artists like Delacroix, Ingres, and Poussin composed a picture, how they used the surface of a picture to take the viewer’s eye to certain points within the picture, whether down or across or along a horizon or from one vertical element to the next. Each step is a carefully staged orchestration of rhythmic movement and a delight to the eye. Completing his course in 1963 Garry and his wife, Sylvia, relocated to the countryside, a small town called Lincoln to the north of Sacramento. His experience in the countryside was both profoundly affecting and somewhat unpleasant. He had built his own house, as a subconscious right of passage, in many ways, for a woodworker, yet missed the pace and vibrancy of urban life. They decided to return to the city, and moved to Alameda and the Bay area.

Soon after a family began to flourish and Garry needed to establish a source of income to support the growing needs. “Squirkenworks”, a jewellery and roach clip manufacturing venture, was that business and it was a fortuitous decision (along with several others) that led to Garry being able to dedicate much of his time to developing his creative output at a workshop and studio.

“Garry would revisit an idea, come back to it ten and fifteen years later. He hates to do repeats. He gets bored. If the piece was ever made in an edition of, say, five, each one would be slightly different because Garry hates making the same thing twice.”

His early works were a series of clocks that Garry built using techniques he had developed in his Jewellery making; the pieces began as metalwork but eventually began to incorporate wood too. The clocks took around a week each to produce and were soon exhibited in New York in the run up to Valentine’s Day; the pieces took on a heart-shaped motif that proved popular at that time.

The work was also selling locally in stores in San Francisco, but he knew that major recognition would only come from selling back East. Although his experience as a jeweller has stayed with him to this day, and his skill with metal is profound, the clocks took him in a new direction, with an entirely new material. Untrained in woodworking, he bought a radial arm saw and a jointer and set to it. In place of the preconceptions that formally trained East Coast woodworkers may have had, he set off with a distinctly Californian “let’s give it a shot” attitude that has permeated his work, and that sets it apart, to a degree, from the mainstream of studio furniture making.

THE NAIL

As Garry’s knowledge of the medium grew, so did his awareness of fine furniture making. True to spirit, he started out making a cabinet that would show that he, too, could make a fine piece of furniture. Beautifully fashioned in padauk with laminated rails and through dovetailing, this cabinet had all the bells and whistles of the craft. In the process of making it, though, he felt the shackles of fine workmanship binding themselves around his ankles and reacted: “About halfway through that piece, I knew I was going to do something.” He took the door off the completed cabinet and, in the words of Arthur C. Danto, “philosophized with a hammer,” driving a nail into the polished surface and bending it over crudely, as an incompetent site carpenter might.

The piece became the infamous Nail Cabinet. Exhibited first in San Francisco, it caused both anger and surprise among the woodworking fraternity and gallery goers alike and it brought Garry fame. But controversy and the piece’s evolution didn’t end there—it was exhibited many times. When the nail was stolen, Garry replaced it, angrily wiring it down. When he became fed up with re-polishing and repacking the cabinet for each new exhibition, he decided to leave it in its exhibition crate, partly visible. This re-imaging of the work became Nail Cabinet Encased.

The latter version references “Fountain”, a famous piece by Marcel Duchamp, who in 1917 took a urinal, titled it “Fountain,” signed it “R. Mutt,” and exhibited it in Paris. Garry turns this on its head. In presenting an existing object—one on which he had spent no more than a couple of minutes—for display in an exhibition, Duchamp challenged what constituted art. For his part, Garry gives us a valuable handmade artefact representing hundreds of hours of patient skill and care and then to a degree destroys it, suggesting that fine craftsmanship alone is not enough, that this in itself can be a cage. In “Encased”, he presses us further, with more questions. What is this object? What is it that a genuine work of art does? What should be in our galleries? Is the idea primary and the execution of no importance? Is skill something to be valued, feared, vilified, or ignored? Garry is waving his hands at Conceptual Art in a most eloquent and timely way.

His process is different than say Judy Kensley McKie,Thomas Hucker or Michael Hurwitz, in that, unlike other furniture designers, Garry tends not to draw his designs before starting to construct them. Instead, he builds in a way that enables him to quickly assemble and reassemble elements of a piece. He will often try out various combinations of components before arriving at his final design.

This method often results in discarded components being used in entirely unpredictable ways in other pieces of work, recycled so to speak, rather than being thrown away completely. It is a fairly faced paced process and has enabled Garry to build an astonishingly large body of work.

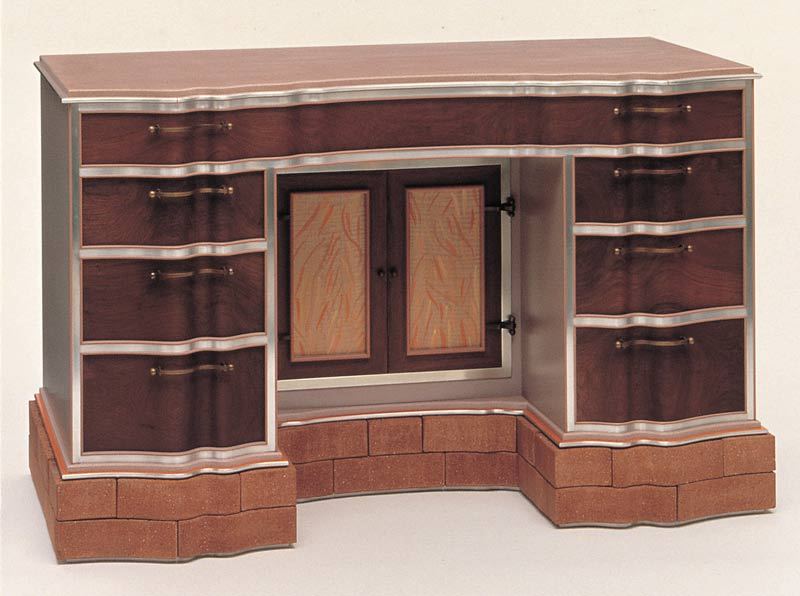

Aware that having a presence back East was essential to his success, Garry was able to get representation with several prominent galleries such the Snyderman Gallery in Philadelphia, where he has had more than one exhibition, the Franklin Parrasch Gallery, the Peter Joseph Gallery, and most recently the Leo Kaplan Modern, all in New York. Doing one-man exhibitions has freed him from dealing with clients and making work on commission. He has also taken part in many mixed exhibitions, including “New American Furniture: The Second Generation of Studio Furniture Makers,” at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston in 1989. Selected participants were invited to make a contemporary version of a piece in the museum’s collection. Garry rose to the challenge with his Boston Kneehole Desk, made with rosewood, aluminium, bricks, antiqued cast bronze, and watercolours. Stunningly contemporary, the piece contrasts the aluminium with the rosewood and highlights the subtle colours of the drawers, the colour accents enlivening the viewer’s experience as his eye moves over the piece, while the bricks form an obvious if slightly challenging plinth. The desk is now in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

When asked about the future, Garry railed against the computer and its potentially damaging effect upon us. When asked what he felt we would be losing, he held up his hands, “These are what we would lose!” An eloquent statement from a man who has used his intellect, his physicality, and his considerable skill to express, through his hands, a lifetime of work. He has a gut-level understanding of materials, a complete competence in processes that now feeds his imagery. He does not need technicians or computer drawings to realize his ideas. He is not controlled by his own personal lack of skill. The knowledge he needs exists within his hands and within his heart.

If you enjoyed this article and would like to read more about Garry Knox Bennett, pick up a copy of the book Furniture with Soul (£19.20 amazon.co.uk), in which 10 of David Savage’s favourite furniture designer makers are featured extensively alongside his favourite up and coming furniture designer makers.