I was 10 years old when I picked up my first plane. It was a wooden hand plane in the school workshop, made with an oiled beechwood body. I remember how heavy it was in my puny arms. But most of all I remember the long silky shavings and the sound that tool made, a kind of high pitched hiss. Like when taking a child fishing for the first time, you damn well have to catch a fish. When you put hand tool in a child’s hand, it has to work.

Since that day I have pursued a love affair with way the cutting edge works into yielding timber. I do not write about tools very often. I find the whole affair of tool fetishism, the shiney new brass Wim-Wams and all that stuff on sharpness distinctly boring. Tools are made for working, for doing things with, for turning timber into something special. Not for sitting on the shelf looking shiny, self satisfied and well sharpened.

Ranges of hand tools that had been created for craftsmen, to use, to earn their living by, were rationalised and cheapened out of existence.

My first plane came as part of a toolkit that my father bought me one childhood Christmas. These were Real Tools and not toys, this was grown up stuff. The plane was a Stanley smoother, a number 4. I can see it in my mind now. Try as I might, I couldn’t get it to work. I read the instructions, I fiddled about with it, I even asked a grown up, but no power on earth could make it work as sweetly as that school workshop wooden plane. I blamed myself, I thought it was my fault, after all, the plane was brand-new, what was it that I was doing wrong? That was the beginning of my fifty year love / hate relationship with tool manufacturers.

Mind you, I was able to buy tools when there were a few tool manufacturers left. Record, Stanley, and Marples, were all big brands and Sheffield steel was something special to look for in a tool. That was before the cost accountants got hold of them, great companies like Marples, and Record, were ruined by small men with calculators. Ranges of hand tools that had been created for craftsmen, to use, to earn their living by, were rationalized and cheapened out of existence. Heroes of this era are men like Alan Reid of Clifton engineering. Made redundant as a manager at Record he saw the opportunity of continuing some of the old lines and products, retaining skills and keeping some jobs going. This was in direct opposition to the general tide of destruction and change, that must have taken some courage.

This was a time when you couldn’t buy a flat plane, what you could buy were “steel bananas”. These planes, made of green uncured castings in Taiwan, were loaded on a boat back to the UK while the castings were allowed “to season.” This is a process that had previously taken several months or a year and now was reduced to a few weeks. Unseasoned castings were machined, packaged and sold to unsuspecting amateurs. For years I watched my students faffing around with plate glass and abrasive trying to reduce the damage these imbecilic manufacturers had done, all in the name of economy. I watched helpless as one guy flattened a Record No 6 plane not once but four times. Each time the casting moving, almost in his hands.

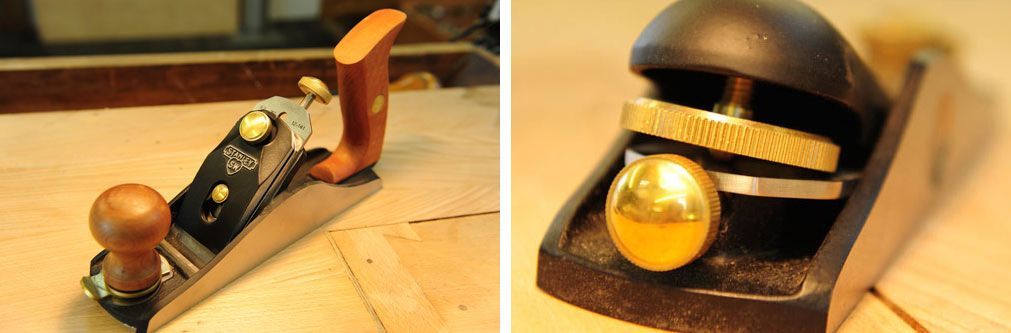

Another hero of this period was Tom Lie Nielsen. Tom saw the same opportunity in America that Alan Reid had seen in Sheffield. Tom’s view was to remake tools from the old Stanley range of hand planes and this he has done spectacularly well. Our workshops are populated with Toms products and though I personally can’t stand the A2 blades that comes as standard, I feel that high carbon steel gives a sharper edge, I take my hat off to his contribution to our world.

Veritas a Canadian company has also made an enormous contribution. Not following traditional patterns and reinventing existing forms they have made some exceptionally awful and exceptionally wonderful tools. I have not bought a plane for many years but if I were buying I will be buying a new low angle Veritas smoother with a high carbon steel blade.

Our workshops are populated with Toms products and though I personally can’t stand the A2 blades that comes as standard, I feel that high carbon steel gives a sharper edge, I take my hat off to his contribution to our world.

I don’t usually get tool manufacturers sending me planes to be reviewed. Over the years I’ve offended many manufacturers. Also magazine editors have seemed to have a distinct absence of testicular fortitude when it comes to criticising advertisers. This removes a great deal of pleasure from the sport. However Nick “lets have some fun” Gibbs, editor of British Woodworking Magazine, sent me two new planes from Stanley. At about the same time as the owner of the website “Woodworking Heaven” pressed upon me two new Chinese manufactured planes. It is always the way, no planes for twenty years then two come along at the same time.

The the whole of my working life I have been looking for properly engineered hand tools at a price that was affordable. I see each year a dozen or so students spending hundreds of pounds on new tools. I see them wanting tools for life but often spending more than is necessary. I hate the brass and shiny “gentleman” tool market. Hand tools are about work, and the more affordable they can be the better. When Malcolm told me that this Chinese Quangshen No6 would cost little money compared to big money for a Lie Nielsen I said O.K send it over.

One must say that on first impressions this is an impressive piece of work. The engineering is everything that one would expect of a Chinese straight copy of the Lie Nielsen number six. There is really no excuse for an engineering company with modern CNC machines to get this side of it wrong. The machining is exceptional, as it should be. The sole is flat, as it should be. The blade made from high carbon T10 steel hardened to RC 63 is very impressive and I do not do “impressed” very often. I am a great fan of high carbon cutting edges and I believe that the Clifton forged steel blade are the very best available. I can’t say how good this blade is as it’s only been with us a few weeks but it shows all the potential of taking an exceptional edge and holding it for a long time.

Having said that, all that I have to say is that I found this plane about as useful as cast steel and brass paperweight. I wouldn’t recommend this plane to anyone however poor they were. This was the unanimous view of the four people who used this plane extensively in my workshop. When I want to test a tool it has to be over a prolonged period. This is where I think so much hand tool design is getting it wrong. The designers and makers of hand tools fail to put them in the hands of people who use them extensively. An amateur reviewer wafting a plane over a piece of wood is very different from using that plane for four or five hours. Do that and you begin to learn what is wrong and what is right.

I can’t say how good this blade is as it’s only been with us a few weeks but it shows all the potential of taking an exceptional edge and holding it for a long time.

When Henry Disston was creating his famous hand saws in Philadelphia in the 1850s he understood the two essential aspects of the tool that he was making. He understood firstly that he was a metal worker creating a complex functional object. A breasted tooth line, a tapered saw plate forged and hardened teeth, a tooth pattern for rip or cross cut. But he also understood that he was a woodworker and that he was creating a hand tool. That hand tool needed an especially carefully designed and carefully made handle. It is the handle that is the point of union between the tool and a craftsperson. It is through the handle that power is transmitted and a “feel” of the job is received. Look at the kind of handle he put on his saws and you see why he built such a successful business.

The handle on the Quangshen plane is pretty enough. Made in Chinese rosewood, shapely enough, but it’s the wrong shape. Everyone who used the plane from Sandra, who is relatively petite, to Lee, who towers over me, said the same thing. “The handle is too small for comfort, it also is not quite at the right angle. It would not be hard to to put this right, what is completely baffling to me is to have done all of the difficult things so well and got this terrifically important but simple thing so completely wrong. I supposed this is the result of taking a western implement and asking a Chinese manufacturer to make it; the Chinese tend to pull their planes rather than push them. Also I found the position of this plane handle to be disassociated from the frog. In almost every other plane I’ve used it is possible to extend the guide finger down alongside the frog, resting it just above the adjustment mechanism, on this plane my guide finger waves around in fresh air seeking a place to sit. Why? Oh why? When you go 90% of the way to get this thing right don’t you give the damn thing to someone who knows how to use a plane, really knows. And do this BEFORE you go into manufacture?

Having said that the little Quang Shang block plane that Malcolm sent was a delight. Give a Chinese manufacturer a CNC machine and watch him change the world. My children are already learning Mandarin. In their time, and I may yet live to see it, Britain and America will probably cease to continue to be “First World” countries so much will change as a consequence of what we see here.

And why should they stay as first world countries if they go on producing products like the new Stanley smoothing plane and block plane? These are quite simply amongst the cheapest and nastiest bit of toolmaking I have come across. This is Stanley’s new attempt to compete in a market that is appreciating a higher quality product. If that is the case then please sell my shares before they dive towards the floor and do the dead cat bounce.

The blade and back iron mechanism is better than I’ve seen on any modern Stanley plane before, but that is not saying much.

Looking at the No 4 “Sweetheart” smoother a little more closely. It is nominally flat as checked on our granite slab. But it is about the first modern Stanley plane to have achieved that accolade. It has, happily, an O.K handle. A crudely formed, ugly, but relatively OK handle. The front knob is, however, far from O.K; unscrewing from the bodies at the slightest twist. You would twist this as it is the locking mechanism of the front adjustable section of the sole. This adjustable mouth allows them to have a cheaper fixed frog but it is a nasty implement which leaves two sharp spikes pointing forward to damage anything, your work, your hands or anything else that got in the way. The blade and back iron mechanism is better than I’ve seen on any modern Stanley plane before, but that is not saying much. The adjustment mechanism is a crude version of that on a Norris, but again better than anything I’ve seen on a Stanley before. Someone has certainly tried to do a better job and produce a better plane, but I sense they just crumbled under the weight of old corporate design mentality. What is this absurd lightweight aluminium cap iron? It just should not be there; sitting in your face all cheap and tacky. Sweetheart? Honey, this is no Sweetheart, this is a dog!

I hate being negative, after that, I tried really hard to find something nice to say about the Stanley 60 1/2 block plane. The old Stanley 60 1/2 was one of the first planes I ever bought and I still have it under my bench now. However this new plane body was appallingly badly engineered, the seating of the blade angled across the width of the plane so that to take a shaving from the centre of the blade demanded a setting strangely angled to one side, this is a problem I have encountered on several Stanley planes over the years, they just do not get the message do they? The cap iron also seems to bear down in a lopsided way on the A2 blade. That about does it for me, chuck it in the bin!

PS

If you’re looking to invest in tools but are unsure what you are looking for and would like advice then feel free to contact the workshop. also you could buy a copy of our ever popular “How to Choose Woodworking Handtools” DVD, for unbiased professional advice.