It’s a big word ‘integrity’. People with integrity fill me with a sense of admiration and awe for whilst I may aspire towards it, I know in my heart that it will always lie a step away from me. People with integrity are the same the whole way through. You know that they’re system of values could never be compromised no matter how uncomfortable the situation. With these rare and wondrous beings, you know exactly where you stand, and that is a sense of great comfort for all of us who have the good fortune to be associated with people of integrity.

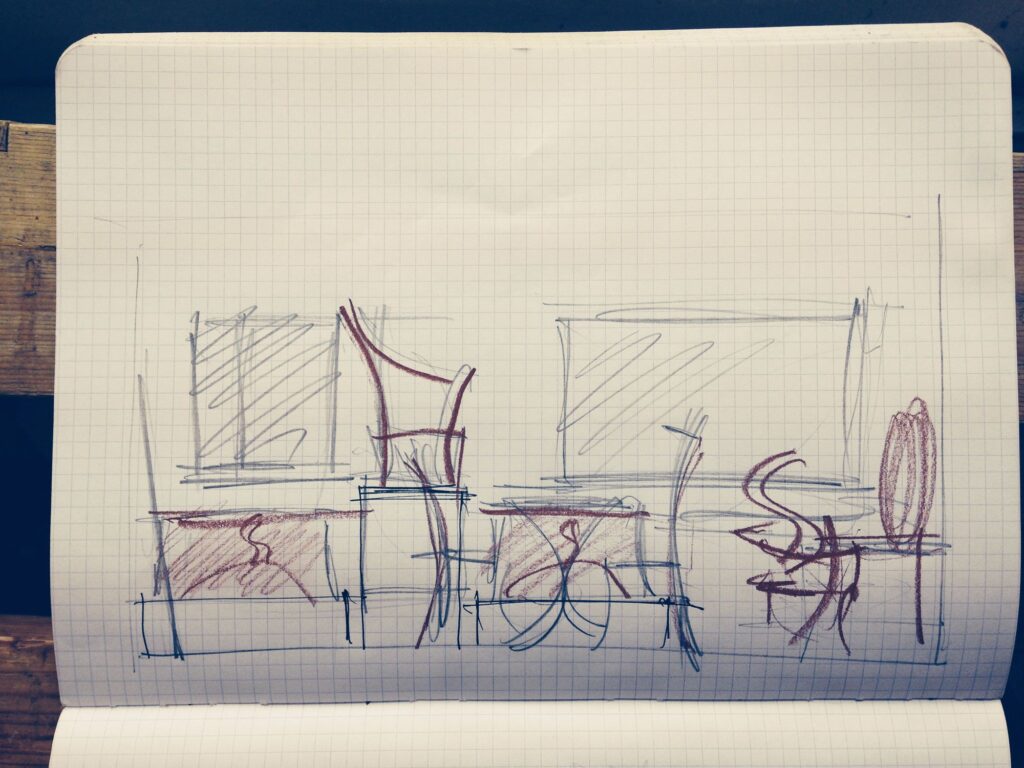

I want to propose that integrity is also an aspect of design. There are pieces of furniture, pieces of good design that display something akin to the quality of integrity. It’s as if again you know where you are with them you feel comfortable with them once you get to know them [which doesn’t mean that on first acquaintance they may not appear difficult or uncomfortable]. Nothing is out of place with them; nothing sets those tiny alarm bells at the back of your head ringing with anxiety. In counselling design students we frequently suggest that one should be true to oneself but what kind of truth is that and how do we know that we are being true to ourselves, how can we tell when we are getting it right, and when we’re getting it wrong. I would suggest that one of those touchstones would be a kind of wholeness a kind of integrity and in this article, I will go on to describe and show how one can work towards this quality in individual pieces of work.

After all it was your idea, you may not especially like it now and it may not have been an especially wonderful idea but it’s still your idea.

I was recently doing the annual spring clean and weeding of the workshop portfolios and was surprised and amused by the disparate nature of the pieces we’d made over the many years that I have been a furniture maker. One works as a professional for different clients with many different requirements. This takes one into areas into which maybe one wouldn’t instinctively tread. I know that clients can be wonderful things, they put bread and butter and occasionally a bit of jam on our table, but they often take us into areas of design aesthetics that we wouldn’t normally go. I know in my case, the worst sin I have committed was to design an especially popular chair which we made and are still making despite my efforts to kill the damn thing stone dead. What’s wrong with that – well nothing except that people like the chair and then want tables and sideboards and this and that to go with it when the idea and inspiration behind the original chair were dead and buried some 15 years ago. So as a professional designer, one is frequently asked to compromise. To make objects that are developments of old ideas and old inspirations.

But then compromise is surely the antithesis of integrity, for is this not at the very root and a part of the very nature of being a professional. By becoming a professional one has admitted to prostitution to provide design ideas for money from then on, it is only a question of price. I am frequently asked – do I mind having clients push and pull me all over the visual spectrum, and my answer is no because clients don’t come to me unless they like the kind of work I’ve done in the past and frequently one can take an idea that was dead and buried 15 years ago and breath new life into it. After all, it was your idea, you may not especially like it now, and it may not have been an especially wonderful idea, but it’s still your idea.

So each piece can be a new statement. Each object you make can have an identity and an integrity that is, in a sense, self-contained. I frequently use the term ” the design base” of an object. This means the set of ideas and visual forms that make up the identity of that object. It may be as simple as a particular kind of moulding used around the top and bottom edges of the cabinet and then developed into another kind of moulding but within the same feeling for the raised and fielded mouldings on the panels of the door.

It’s as if you are attempting to make a symphony in visual forms. A symphony will open with a particular refrain – Dah Dah Dah Dum. This will be repeated and developed in the opening of the symphony, so you become familiar with it. Then in the body of the work that refrain – Dah Dah Dah Dum will be turned inside out – pulled apart, looked at upside down, twisted, reversed but it will still be – Dah Dah Dah Dum. At the end of our symphony, we are returned to the opening refrain; we are reassured and reintroduced to our old friend – Dah Dah Dah Dum.

In this way, we use the Design Base or Dah-Dah-etc to develop an identity for the object whatever the core idea is it is expanded turned upside down and fitted to every nook and cranny of our object. Another way of approaching this is modular thinking here a single solution can be repeated in several different ways to create a visual whole. This approach is a favourite with young designers as it enables them to fill up a portfolio with a range of related objects giving the impression of a mature resolved designer when the truth is the whole collection is only based on one idea. The other common problem frequently seen at exhibitions is applying the contents of the router catalogue here and there this with relentless efficiency. The danger with design base thinking is that if we are using pretty conventional forms within that design base, it can be so safe, so dull and so boring. One of the features of good original design is that it will not repeat old worn out refrains, it may recycle them, it may reinvent them, but by the very nature of the business, good designers are always getting bored with their ideas so we will slowly but inevitably always move on.

Each object you make can have an identity and an integrity that is in a sense self contained.

Look how Martin Grearson has treated the simple elements within the Maple Dining Table shown here. First, we have the main angular elements of the form shown in the base of the pedestal. This is echoed in the way the corners of the tabletop are removed. See how the ebony detailing which is used around the extreme bottom of the table is used around the extreme top, around the edge of the table. Note how this detailing is chamfered very simply around the base of the pedestal to echo the forms used in the design base so far. But now Grearson introduces six faceted columns. Without this element, we would have a relatively dull and uninteresting design. Still, Grearson takes the risk of putting in an element that is both contradictory but also has the potential of becoming harmonious. Each of the two groups of columns is arranged in a format reflecting the existing design base. They are faceted to catch the light in narrow vertical bands again contributing to the integrity and wholeness of the piece. Had these column’s been merely turned, I do not believe it would have worked half as well. Around the base of each column is a small faceted detail that leads the eye out onto the horizontal surface of the pedestal of the table. A simple and unified design, yet it has richness and complexity within it.

Another visual risk-taker is Andrew Varah, who is clearly developing an image of Chinese Chippendale and bringing it into the 20th Century. Here Varah has taken disparate forms. If you look at the back of the chair which has a square latticed back arranged in a diamond form and compare it with the forms used for the underside of the seat which are radiused forms slightly reminiscent of Gothic buttressing we see two almost conflicting elements to the design base yet how well they are worked together. Here Andrew Varah has used a simple unifying element which is the size of the components. I would guess that the dimensions of the components making the back lattice would be somewhere between 10-15 mm. That size is used again and again throughout the components of the chair. The legs which may be at a guess 30 or 40 mms square are divided in three, so we again come down to something around the 10 mm mark. The seat itself is made up from a curved relatively thin board as are the supporting struts beneath it. The stretchers between the front and rear legs have a depth that is more than our design base 10 – 12 mm, but I would guess that it would have a thickness that fits in with my idea. This is a chair that is all a visual whole. Complex and rich and visually very successful. I think it’s a mark of the maturity of the designer that he’s been able to take such disparate elements and weld them into a successful visual whole using a relatively simple device. A less experienced designer might not have been so successful.

So seek within the design of each piece to find a theme and echo it around the piece of furniture. If you’re attempting to be more daring, integrate a second theme but be careful to weld the two themes together in a way that is simple and coherent. Visual integrity, like the integrity in human beings, is relatively straightforward but not always easy to find.